It took a friendly poker game at a medical school to introduce two revolutionary scientists who have brought to Houston a more environmentally friendly way of making the chemicals that are part of our everyday lives.

The entrepreneurs and co-founders of Solugen, chief executive officer Gaurab Chakrabarti and chief technology officer Sean Hunt, hatched their plan to “revolutionize the chemicals industry” and found the ideal location in Chakrabarti’s childhood neighborhood in the Brays Oaks Management District.

Solugen’s facility at 14549 Minetta is at the former home of the Marcus Oil and Chemicalpolyethylene wax facility plant, where a tank explosion in 2004 caused permanent closure.

Solugen’s facility at 14549 Minetta is at the former home of the Marcus Oil and Chemicalpolyethylene wax facility plant, where a tank explosion in 2004 caused permanent closure.

In contrast, Solugen’s first-of-its-kind biomolemanufacturing process harnesses the power of nature to produce life’s essential materials, all with little to no emission or waste. The facility presents no risk of explosion or leakage, the company says, thus bringing a welcome change to the neighborhood.

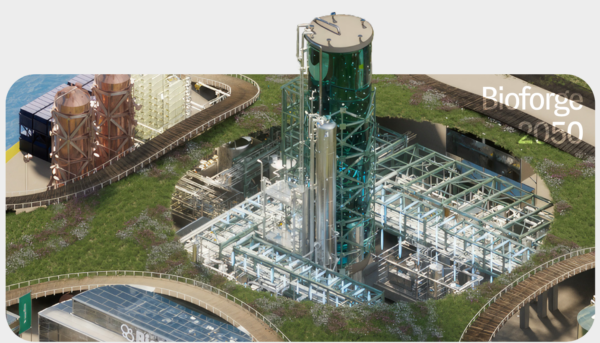

The campus is Solugen’s lead research and development facility and includes a 10,000-ton demonstration-scale chemical plant (nicknamed the “Bioforge”), over 20,000 square feet of lab space, and 10,000 square feet of warehouse and storage space for their product.

Solugen said its innovative technology platforms have attracted a world-class team of scientists, including members of Nobel Prize-winning teams. The company has grown to more than 200 employees.

Its novel patented production process makes green alternatives that replace chemicals traditionally made using petroleum and natural gas — using corn sugar straight from the Midwest. These chemicals are used for a variety of industries including energy, agriculture, water treatment, construction, homes, cars, and cleaning.

Solugen touts itself as “the world’s first sustainable molecule factory,” saying its process is complex, scientifically sound, and leads to significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

The sustainably sourced plant-based feedstock is fed into what Solugen calls a “cell-free enzyme reactor.” This is the giant column that can be seen in the middle of the plant and is essentially a giant bubbling cauldron of corn syrup.

This is where the engineered enzymes (nature’s incredibly efficient workers) begin the highly selective conversion process from the corn sugar with low inputs of energy required.

Rendering

After that, it is fed into another reactor where “engineered metal catalysts” finish the job at significantly lower temperatures than traditional petrochemical processes.

The efficiency of Solugen’s technology means that the same type of chemicals to which customers are accustomed can be manufactured cheaper, more sustainably, and with a reduced operational footprint. That’s why the Bioforge looks nothing like the other chemical plants you might be used to seeing on the industrialized parts of east Houston and Harris County.

Solugen’s team proudly notes that the method creates safer conditions for humans and the planet.

The company was founded in 2016 after the founders placed second at an entrepreneurship competition at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In just over six years, the company has raised more than $420 million in venture capital investment (film star Leo DiCaprio is one of the investors), built a commercial-scale plant, and was named one of the world’s most innovative companies by Fast Company Magazine last year.

So what does building a brighter future look like for Solugen? It’s on a bold mission to “decarbonize the physical world”— a future where every molecule that makes up the world around us can be made sustainably.

To achieve this, Solugen has plans to create a network of Bioforges around the country and around the globe. Employees are constantly researching even better ways to improve the efficiency of their process by using artificial intelligence, diversifying the feedstock (they are exploring opportunities to use recycled cardboard!), and what entirely new molecules could be made using this process.

Solugen plans to continue expanding operations and while committing to being a good neighbor through outreach to local schools, businesses and the management district.

— by Arlene Nisson Lassin